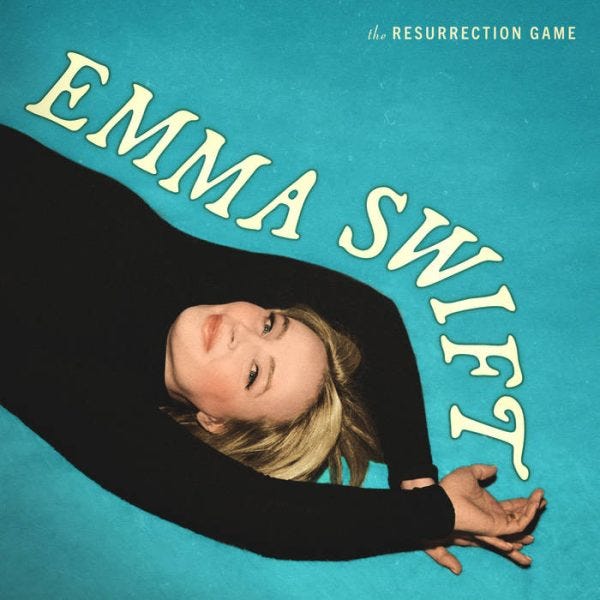

ALBUM REVIEW: Emma Swift “The Resurrection Game” -- Where the Brutal Becomes Beautiful

Originally Published on Americana Highways

Emma Swift’s The Resurrection Game follows in the tradition of her heroes, singer-songwriters like Sandy Denny and Marianne Faithfull, artists who transformed personal struggle into compelling music. As Swift’s first album of original material, it represents an important and promising step in her artistic development.

Swift herself describes this collection as “a bummer of a record,” a characterization that proves accurate, if reductive. Written primarily between 2022 and 2024, these songs emerged from the aftermath of what Swift describes as a seven-week “nervous breakdown” that resulted in her being sectioned in her native Australia. What followed was over a year of recovery—a period Swift characterizes as “very fragile”—during which she processed her experience through therapy, medication, and ultimately, her art.

The album succeeds in its stated goal of transforming personal pain into music. Swift’s voice remains her strongest asset, providing clarity and emotional weight to lyrics that confront difficult subjects directly. The juxtaposition between her crystalline vocals and the album’s heavy emotional content creates tension that works well on the stronger tracks, though it occasionally feels forced on weaker material.

Producer Jordan Lehning has created arrangements that serve Swift’s material well. The album’s sonic landscape aims for lush orchestration that creates space for Swift’s voice while providing musical support for the lyrics. The production occasionally leans too heavily into the album’s melancholy, making some tracks feel overwrought where a lighter touch might have been more effective.

Swift’s core band — Spencer Cullum (pedal steel), Jordan Lehning (keys) and Dominic Billet (drums), Juan Solorzano (guitar) — are largely experienced Nashville hands, a group who recently has started to play together as Echolalia. They’ve all known each other for years, played together at different times but never altogether as a band. Cullum’s pedal steel work provides some of the album’s most memorable moments. Cullum, whose extensive experience includes work with Miranda Lambert, Kesha, and Little Big Town, brings a deft touch to Swift’s material. His playing adds the right Americana flavor while maintaining the album’s emotional consistency, particularly on tracks like “How To Be Small” and “Beautiful Ruins.”

The addition of a string section—featuring Annaliese Kowert and Laura Epling on violin, Betsy Lamb on viola, and Emily Rodgers on cello—brings classical sensibilities to the album’s texture. Rather than simply adding orchestral grandeur, these players approach the material with precision and emotional intelligence, creating arrangements that enhance the songs’ emotional impact without overwhelming them.

Swift’s approach to addressing mental health and personal crisis through her songwriting is both brave and necessary. As she notes, “I believe that there is a space for songs about real pain. In this moment in time, we live in a world where we’re encouraged to anesthetize what ails us by any means possible. But this record is more about spending time with your sadness, of leaning into that sorrow and facing it head on.”

This philosophy permeates every track on The Resurrection Game. Swift doesn’t offer easy answers or false comfort; instead, she presents a clear-eyed examination of suffering that acknowledges its reality while searching for meaning within it. On “No Happy Endings,” she confronts mortality and impermanence with unflinching honesty: “The world’s a spinning time bomb / That there’s no denying / There are no happy endings / But baby I’m trying.” Yet even in this stark assessment, there’s defiance—an insistence on connection despite inevitable loss.

Her lyrics cut straight to the heart of complex emotions without resorting to cliché or sentimentality. In “How to Be Small,” she captures the vulnerability of depression with devastating simplicity: “I am so terribly lonely / How are things with you?” The contrast between profound isolation and casual social convention captures the disconnect between internal experience and external performance that defines much of modern suffering.

The album’s title track and songs like “Nothing and Forever” and “Catholic Girls Are Easy” showcase Swift’s ability to find universal truths within personal experience. In “Beautiful Ruins,” she transforms the aftermath of trauma into something almost mythic: “I come from the place, the place of many crows / And I’ve told them all my stories / And I’ve let them pick my bones.” The imagery is both visceral and poetic, suggesting both destruction and renewal.

Swift gives us songs that go beyond her personal mental health crisis; they are explorations of humanity that will resonate with anyone who has faced loss, grief, or the kind of existential questioning that comes with life’s darker moments. The album’s closing track, “Signing Off With Love,” perhaps best encapsulates this duality: “Is this how the end of the world is supposed to feel?” Swift asks repeatedly, but the act of asking—and the love in the song’s title—suggests that even in endings, connection remains possible.

Swift’s belief in “the redemptive power of art” (as she puts it) is evident throughout The Resurrection Game. She describes her process as attempting “to alchemize the experience. To make the brutal become beautiful.” This transformation is perhaps the album’s greatest achievement—it takes pain that could have been purely destructive and channels it into something that offers both artist and listener a path toward healing. In “The Resurrection Game,” she literally excavates the past: “In Calistoga, where the redwoods grow / I have come to, to excavate your bones,” transforming the archaeological metaphor into something deeply personal yet universally resonant.

The Resurrection Game is quite different from Swift’s previous album, 2020’s Blonde on the Tracks, which featured her interpretations of Bob Dylan songs. Where that earlier effort demonstrated Swift’s ability to reinterpret existing material through her own perspective, this new collection presents her original songwriting. The contrast is notable: Blonde on the Tracks benefited, of course, from classic source material and allowed Swift to focus on vocal interpretation, while The Resurrection Game requires her to carry the full weight of both songwriting and performance.

The Americana genre has long accommodated artists wrestling with personal difficulties, from Hank Williams’ confessional honesty to Jason Isbell’s examinations of addiction and recovery. Swift’s contribution fits this tradition, addressing mental health with directness while drawing on familiar themes of suffering and resilience. The album works best when Swift avoids overstatement and lets her natural voice carry the emotional weight.

The Resurrection Game succeeds as both personal statement and artistic milestone. Swift’s willingness to address difficult subject matter directly demonstrates real courage, and her voice remains compelling throughout. While the album has its uneven moments, it achieves something meaningful: transforming private pain into music that speaks to universal experiences of loss and recovery. The stronger tracks—particularly “The Resurrection Game,” “Beautiful Ruins,” and “How to Be Small”—reveal Swift as a songwriter of genuine talent, capable of finding poetry in darkness without resorting to easy sentiment. For listeners drawn to honest, emotionally direct music, The Resurrection Game offers substantial rewards and suggests that Swift’s journey as an original artist is just beginning.

Enjoy our previous coverage here: Emma Swift’s Blonde Ambition